|

Haiti and the School of the Assassins

November 28, 2006

|

News

HaitiAction.net

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

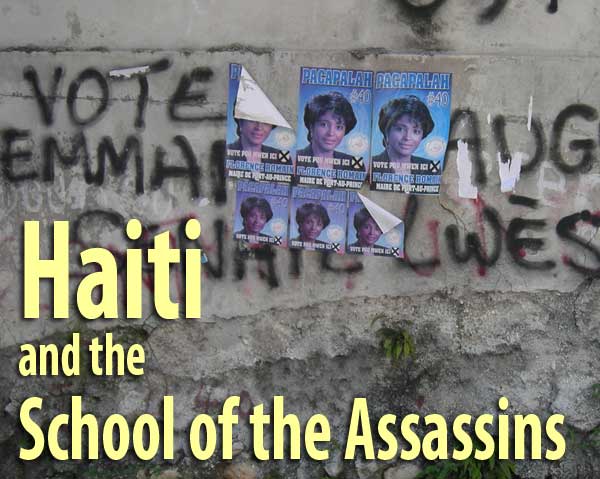

| A legacy of death. Florence Romain — the daughter of SOA graduate Franck Romain — will run for Mayor of Port au Prince in next week's election on December 3, 2006 - photo: ©2006 Randall White |

Haiti and the School of the Assassins

School of the Americas: The Haitian Case

by Adrianne Aron

Thanks to School of the America's Watch's (SOAW) annual Vigil at the School of the Americas (SOA), the persecution of the religious community in El Salvador during the 1980s is not forgotten. Every year they commemorate the massacre that the Jesuit Provincial called "an act of lavish barbarity," when six Catholic priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter were murdered on the campus of the University of Central America in San Salvador, by government soldiers trained at the School of the Americas.

In Haiti, a number of equally barbarous events carried out by SOA graduates are not so well known, and have been neglected by world attention. The perpetrators are still free, and in some instances, still wielding power. It's time we took notice.

September 11: Haiti

A case in point is Haiti's September 11, a day of infamy in 1988 when SOA alumnus Franck Romain, then Mayor of Port-au-Prince and leader of the brutal Tontons Macoutes, orchestrated a siege of Saint Jean Bosco, the parish church of Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide. As Fr. Aristide was saying Mass, armed thugs broke down the doors of the church, shooting and slashing their way to the altar, and torching the building, leaving 50 people dead and 77 wounded. "People were clawing at the doors, hiding behind the altar, diving under the pews, anywhere," a survivor told journalist Mark Danner. Those who tried to flee were stoned or clubbed, and Fr. Aristide narrowly escaped with his life. Afterwards, as in El Salvador after the massacre at the UCA, the killers bragged about their deeds. On TV, they vowed to finish off Aristide, promising that if he celebrated Mass again in Haiti, only corpses would be present in the church.

Aristide, of course, was later drafted by Haiti's masses to run for President of the country, and was voted into office by a landslide. He served as a popular democratic leader until he was forced into exile by a US-backed coup d'etat carried out by Haitians trained at the Creole-language version of the School of the Americas. The Creole-SOA, at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, was the latest metamorphosis in a process begun in 1934, when the United States, after two decades of occupying Haiti, created the Garde d'Haiti to take over from the Marines, on the model of the Nicaraguan National Guard established the year before to secure the dictatorship of Somoza.

The CIA, the Department of Justice, the Pentagon-various U.S. agencies-have had a hand in creating and training police and military forces in Haiti. To fight the War on Drugs in 1986, for instance, the US created the National Intelligence Service (SIN). Staffed by Haitian Army officers, SIN took as its principal task the persecution of the followers of Fr. Aristide-the Lavalas movement-and it wasn't long before Haitian soldiers wielding machetes and guns conducted a savage massacre of voters in Port-au-Prince. After Col. Gambetta Hyppolite, a graduate of the School of the Americas, led a parallel attack on polling places in the city of Gonaives, the US Congress determined that the human rights abuses were so egregious, military aid to Haiti should be suspended. Congressional aid was stopped, but the CIA picked up SIN's tab, giving the agency a million dollars a year for equipment and training. Washington looked the other way when SIN officers were caught trafficking in cocaine, and Congress raised no objections to the terrorism, including torture, being carried out against Aristide's supporters.

Training for Regime Change

In 1991, Jean-Bertrand Aristide was inaugurated as President of Haiti. Eight months later, CIA-operative Michel Francois, Chief of Haiti's National Police and founder of the Anti-Gang Unit that routinely tortured prisoners to death, led a coup that drove President Aristide from office. Francois was a graduate of Ft. Benning's Infantry School. Philippe Biamby, a fellow leader of the coup, had also been trained at Ft. Benning's Infantry School, while Raoul Cedras, the coup leader who took control after the democratic government was ousted, was a graduate of Ft. Benning's School of the Americas.

During the Cedras regime, on September 11, 1993, Sacre Coeur Church in Port-au-Prince was commemorating the fifth anniversary of the massacre at St. Jean Bosco. In full view of the media and human rights observers, a paramilitary death squad dragged businessman Antoine Izméry, a prominent Aristide supporter, out to the sidewalk, and shot him through the head. The following year, Aristide supporter Father Jean-Marie Vincent was gunned down in Port-au-Prince. When he'd led a peasant land reform movement some years before, the massacre of hundreds of peasants had made no impression on Washington, nor had the violent death of more than 5,000 people during the bloody Cedras years attracted much notice. The assassination of a priest, however, got attention. The US Department of Justice took action to bring about "democratic policing" in Haiti, by establishing a new program, the Investigative Training Assistance Program. Trainees were recruited largely from the Haitian Army, hand-picked so as to exclude officers loyal to President Aristide. Among those selected for this new "democratic policing" were death squad members, narcotics traffickers, and officers known to have practiced torture, yet due to "time restraints" their curriculum could not cover instruction in human rights, appropriate use of force, or non-lethal intervention techniques. A year after the program was founded, the number of trainees was doubled, to 3,000, and with such a large number, the US saw a need to open a new facility, which they placed not in Haiti, but in Missouri, at Ft. Leonard Wood. Thus was born the Creole-language version of the School of the Americas. According to the program director, recruits were flown in for training, "at an accelerated pace without sufficient supervision, equipment, or logistical support." Deployed, they were left to their own devices, "sometimes with dire consequences."

"Dire consequences" translated as extravagant human rights violations for the people of Haiti-not only by the poorly trained Ft. Leonard Wood graduates, but by students from the more efficient training program in Ecuador, sponsored by the US Special Forces. That is where the notorious Guy Philippe, a staunch admirer of Augusto Pinochet, was schooled. In 2000, Philippe had to flee the country after he and fellow alumni of the Ecuador academy were caught planning a coup that had as its aim the resurrection of the Haitian army, which President Aristide had disbanded. From abroad he continued staging deadly incursions into Haiti, terrorizing the Central Plateau with raids and massacres. February 2004 found him in Santo Domingo, well positioned to take control of a shipment of thousands of high power weapons sent from the United States as foreign aid to the Dominican Republic. On February 29, 2004, US personnel entered the presidential palace in Port-au-Prince and removed President Aristide at gunpoint, warning that if he did not cooperate, a heavily armed Guy Philippe would be coming to kill him and would produce a bloodbath in Haiti.

Under the U.S.-sponsored coup regime, United Nations troops were dispatched to Haiti as "peacekeepers," but like the Haitian army before them, they gave no protection to the poor, and no protection to religious people dedicated to serving the poor. Jean-Bertrand Aristide had once said, "The crime of which I stand accused is the crime of preaching food for all men and women." This was the crime also of Fr. Gerard Jean-Juste, who operated a soup kitchen for children in Port-au-Prince, at his parish church, Saint Claire. In October 2004, hundreds of children witnessed their priest being taken away by heavily armed masked men. Fr. Jean-Juste was thrown into a cramped, unlit, filthy jail cell, where the treatment was brutal and the conditions so unspeakably horrible that when a cellmate died, the guards waited twelve hours before removing the diseased corpse from the crowded cell. Hundreds of Haitians, the majority of them pro-democracy political prisoners, endure conditions like this in Haitian jails. Fr. Jean-Juste was eventually released, but was again taken into custody a few months later, "for his own safety," following renewed violence against him and his church. While the bullets were flying at Ste. Claire, United Nations Peacekeepers ignored the priest's appeals for protection, but they later came for him, and turned him over to the Haitian police, who imprisoned him for six months. A Chilean, Eduardo Aldunate, was appointed second-in-command of MINUSTAH, the UN force in Haiti. Earlier in his career he had been trained in torture at the School of the Americas in Panama, and plied his trade in Chile, under Pinochet.

Persecution of Religious Figures

Why has the church been the target of so much repression in Haiti? One answer lies in the 1980 Santa Fe Document, a position paper of the Reagan administration which spelled out the need for US policy to oppose clergy who embraced liberation theology. Their Preferential Option for the Poor had to be countered, Reagan advisors declared; it was critical of productive capitalism. In Haiti, Frs. Vincent, Jean-Juste, and Aristide, like the priests and nuns in El Salvador, strived to rectify the structural violence of a system that leaves the majority of the people of the Third World unfed, uneducated, unhealthy, and unfulfilled. For that they were tortured, raped, exiled, imprisoned, murdered-countered.

At least since the time of Duvalier, churches have been the target of violent attack by the armed forces in Haiti. Papa Doc expelled entire religious orders from the country, and was so vicious that he was actually excommunicated for a time. The secret police of his successor, Baby Doc, tortured a young Fr. Jean-Juste in 1971, for refusing to pledge allegiance to the dictatorship. But the Church hierarchy has itself attacked religious figures, making its own contribution to the repression. By ordering Fr. Aristide out of the country, for example, the Vatican reinforced the agenda of the Haitian armed forces and the Haitian elites whose interests they protect. Similarly, when the Haitian Archbishop delivered a homily in 1990 attacking the newly elected President Aristide as a "socio-bolshevik," his contempt for the democratic process left little to the imagination.

Structural Violence

The Vigil at the School of the Americas was begun as homage to the priests who were assassinated in El Salvador for having named and denounced as sin the social structures that keep the masses in Latin America in a condition of servitude and misery. The fact is, however, that to honor the Jesuits' struggle against the structural violence that pervades the Third World-the institutionalized neglect of people's basic human needs for food, decent housing, clean water, medical attention and the like-one could just as easily trace the history of labor leaders, health workers, student activists, teachers, advocates for women's rights, agricultural workers, journalists-any of the groups in civil society that work for social and economic justice-and the story would be equally bloody, equally tragic, equally illuminating. Even a study of those once-removed from direct activism would be enlightening. Marjory, a girl interviewed during a human rights survey in Port-au-Prince, was one of 35,000 Haitian girls and women who were raped in the 22-month period after the 2004 coup. She was targeted because her father's trade union organized against a wealthy businessman, and because her parents belonged to Lavalas, the political party led by Jean-Bertrand Aristide. One could even trace the history of those who are twice-removed from direct confrontation with the anti-democratic forces, like the researcher from Wayne State University who conducted that survey of human rights in Haiti. When the results of the study were published in the British medical journal The Lancet, the author began receiving telephone calls threatening her with rape, evisceration, and death; she received a dead rat in the mail; she was told, "You are a dog, you should die!"

Just as religious workers are not unique in their victimization by the forces of repression, so the victimizers are not uniquely linked to the School of the Americas. Perpetrators of atrocious human rights crimes need not have received direct training from the School of the Americas to have developed the sense of entitlement that allows for the abuse and violent dehumanization of others. They could have learned from the various other permutations of the school-the one in Missouri, the one in Ecuador, the training programs sponsored by military and civilian agencies alike that have as their aim the advancement of the political and economic interests of the United States, and that, in the name of "National Security," support the structural violence that bludgeons the Third World. Like the gulags of detention and torture, the many tentacles of repression are indifferent to national borders. When the School of the Americas was located in Panama, French military officers who had developed counterinsurgency strategies in Vietnam and perfected them in Algeria, came to the U.S. school in Panama to train Latin American soldiers in torture techniques. Their mentors, of course, had come from Germany, from Hitler's SS.

A Life of Dignity and Peace

Training centers like the School of the Americas, or the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation as it is now called, or the International Law Enforcement Academy recently opened in El Salvador, must be exposed and resisted if any progress is to be made in creating a just and humane world. We may begin with the eradication of torture, but we must recognize that torture is only one weapon in a massive arsenal of repression that stretches across nations, oceans, and continents. Such things as the control of communications and food and water sources, the manufacture of fear, the demonization of enemies and curtailment of civil rights and activities, are equally devastating to the individual's ability to flourish in life and remain attached to the human bonds that sustain community. If we strive for peace and justice, our aim must be to dismantle the entire destructive apparatus, piece by piece, practice by practice, device by device, and erect in their place institutions and societies that serve their people. That was the aim of the Jesuits whose memories we honor in the annual Vigil at the School of the Americas. Because that was their aim, they were not merely shot to death; their brains were blown away by high power rifles, in an attempt by the forces of repression to kill their ideas. But ideas do not die. Their same ideas are being advanced today by people everywhere who struggle for a life of dignity and peace-like the people of Haiti who refuse to cave in under the heavy repression, and the people at the SOA vigil, who demand an end to the teaching of terrorism. We are the living proof that ideas do not die.

Adrianne Aron, Haiti Action Committee